The new bigots?

The counter at the cake shop has become an unlikely front in America's ‘culture wars’

By Bruce T. Murray

Author, Religious Liberty in America: The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective

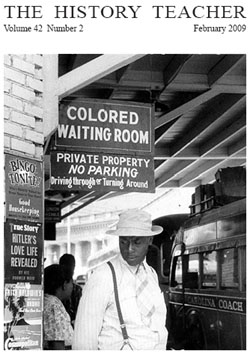

It's open season on religious people and business owners who refuse to cater to same-sex weddings, the conservative commentators complain. The bakers, florists and wedding photographers who conscientiously object to taking part in such transactions are intolerant bigots – on the level of the white racists who refused to serve black patrons in the segregated South, the liberal pundits accuse. Furthermore, laws such as Indiana's Religious Freedom Restoration Act are nothing more than a cover for institutionalized discrimination, according to this view.

|

| Religious Liberty in America was reviewed in The History Teacher. |

Amidst all of the hyperbole, it can be challenging to comprehend the respective points in this tempest. When the issue is framed at the broadest level, the viewpoint of “no discrimination” – in any shape or form – seems obvious enough. This is a basic American value. So then, why discriminate? Why would this ever be acceptable for any reason, religious or otherwise?

In this context, comprehending the conscientious refusal requires framing the issue at a slightly less general level. Understanding religious people requires more nuance and particularity than the broad-sweeping claims and accusations. Rowland A. Sherrill, the late professor and chair of Religious Studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, called for a better understanding of what he ironically termed, “the religious creature.”

“Let’s not beat around the bush, our first response to people who are religious – or religious in ways other than our ourselves – is to be irritated,” Sherrill said at the lecture series, Journalism, Religion & Public Life, sponsored by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The negative stereotypes operate at many sub-levels: “The corollaries are that religious people are superstitious, stupid, exhibit deep dependency traits to a neurotic level; they belong to an archaic world, are anti-intellectual, are absolutist and dogmatic, brainwashed, or are under some kind of mind control,” Sherrill said.

Sherrill confronts these stereotypes in his lecture, “Understanding People of Faith,” and he offers alternate frameworks for both the religious and non-religious alike. Sherrill's lecture forms the basis of Chapter 2 of the University of Massachusetts Press book, Religious Liberty in America: The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective by Bruce T. Murray. In the book, Murray analyzes the many contours of religion in American life, the “culture wars,” and the related legal issues. The book also covers the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, enacted in 1993 in response to the Supreme Court's decision in Employment Division v. Smith.

“Religious Liberty in America engages a complex set of issues, especially welcome when matters of faith and politics have become so prevalent in public discourse. ... Murray covers a lot of ground in this relatively short book. In general, he nicely summarizes divergent views on religion's role in public life, capturing key moments in the development of religion in the formation of the nation, the U.S. Constitution, revivalism, and the origins of civil religion, exploring linkages between religion and the concepts of nationhood and belonging. The book provides short and readable summaries of this terrain for readers seeking succinct discussion of the issues.”

— David A. Reichard, California State University Monterey Bay, The History Teacher, February 2009

Religious Liberty in America is available at libraries throughout North America, and it may be purchased from the University of Massachusetts Press.

Read about the author on SageLaw.